Think of a cycle shape as a series of ups and downs, such as up-down-up-up-down-up-down (1011010). There’s only one number that returns to itself after those operations. In the case of 1011010, it’s

\cfrac{2^0 3^3 + 2^2 3^2 + 2^3 3^1 + 2^5 3^0}{2^7 - 3^4} = \cfrac{119}{47}.

which is not an integer. If you’re uncomfortable with applying the Collatz rule to fractions, just use the numerator for the odd/even test, then see if you can take \cfrac{119}{47} back to itself, while confirming that the shape you follow corresponds to 1011010. The first step would be (3 \cfrac{119}{47} + 1)/2 = \cfrac{249}{47}.

The only shape known to return an integer to itself is: up-down (10). If you start with 1 and go “up-down” you go 1 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 1. Actually, the shapes 01, (10)^*, and (01)^* also return 2, 1, and 2 back to themselves, respectively.

If we could rule out all the other shapes, we’d have proved the Weak Collatz Conjecture (no cycles).

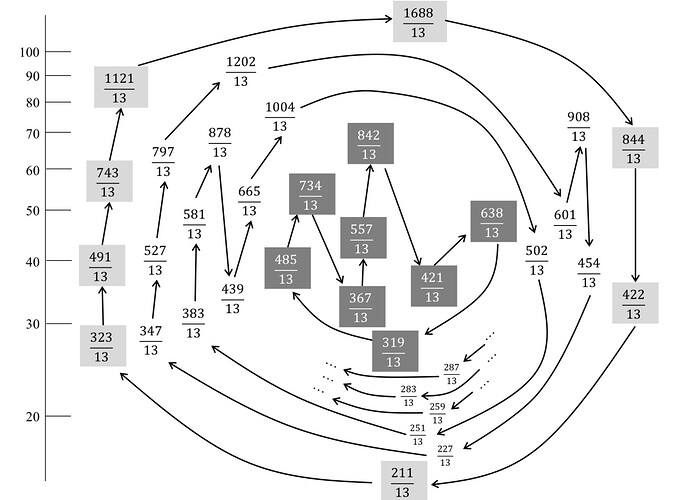

Here are all the cycles of length 8 with 5 ups (odds), along with the members drawn in:

I think it’s interesting to look at the individual numbers in the chart. Usually, we look at concrete numbers to double-check our abstract assertions or sweeping generalizations, but occasionally it’s the other way around – studying the numbers can reveal a pattern.

Some interesting things to observe:

-

All members of (8, 5) cycles fall in a range between 16 and 130.

-

No (8, 5) cycles consist of integers. That is, none of the numerators are ever multiples of 13. If you think of the numerators as random (and heck, I don’t blame you!), you will attribute “no (8, 5) cycles” to bad luck. I mean, come on (8, 5), you had seven chances to make some numerator that’s a multiple of 13 ! (Note: 7 chances, not 56 chances; easy math says, “If one member of a cycle is an integer, they all are.”)

-

Two cycles seem distinguished: (1) the outer ring, called the circuit, and (2) the inner ring, called the high cycle. The circuit has the “highest of all cycles’ high members” and the “lowest of the low members.” The high cycle has the “highest of the low members” and the “lowest of the high members.”

-

The high cycle has two members that we can strategically subtract from each other: \cfrac{485}{13} - \cfrac{421}{13} = \cfrac{2^6}{13}, which can’t be an integer, since 13 is odd. If the high cycle consisted of integers, this pair’s difference would also be an integer … which it isn’t … so it doesn’t.

-

It turns out every high cycle of length k has two members whose difference is \cfrac{2^{k-2}}{2^k - 3^x}. So no high cycle (on any other chart) is a Collatz counter-example.

-

Other cycles also have pairs of members with this property, but it always seems to be an “accident.”

-

Consider the first two members of the circuit, \cfrac{211}{13} and \cfrac{323}{13}. Their difference is \cfrac{112}{13} = \cfrac{2^4 \cdot 7}{13}, which is an integer only if \cfrac{7}{13} also is. But it isn’t, so this circuit doesn’t consist of integers.

-

If you try this for larger circuits, the numerator 2^{k-x}-1 (in the above case, 7) always seems smaller than the denominator 2^k - 3^x (in the above case, 13). But proving this currently requires Baker’s heavy artillery showing the denominator grows almost as fast as 3^x … that is, no near collisions between 2^k and 3^x are possible.

-

What about taking three members of a cycle, say a, b, and c, and showing that a+b-c is of the non-integral form \cfrac{2^i 3^j}{2^k - 3^x} ? That would rule the cycle out. Or n members, or all members? I’ve studied the heck out of this. When I look at increasingly big cycles, I always seem to find one that resists this sort of reasoning.

-

One thing circuits and high cycles have in common is that members of the “subtraction pair” always have very similar parity vectors. For example:

Circuit a: 1111{\color{red}1000}

Circuit b: 1111{\color{red}0001}

High cycle a: 101101{\color{red}10}

High cycle b: 101101\color{red}{01}

In both cases, they share a long prefix. I figured out that if the shared prefix is half the length (or more), then Baker’s theorem is strong enough to rule the cycle out. (I haven’t written this up … should I? Is it known?) Anyway, I like this result, because it addresses all kinds of other circuits, such as regular ones like (110)^* 0^*:

Regular a: 110110110110{\color{red}11000000}

Regular b: 110110110110{\color{red}00000110}

-

It’s sobering, though, that “almost no” cycle shapes are self-similar enough. A randomly-selected parity sequence will have no two rotations with a shared prefix longer (roughly speaking) than \log_2(k), much lower than the needed k/2.

-

It’s also possible to add and subtract members across different cycles, looking for patterns and conclusions. I’ve had limited success with that as well, but who knows?

-

See anything else in the chart?