Define:

Depending on the congruence class of d mod 6, either \mathcal{J}_{1} (for d \equiv 1 \pmod{6}) or \mathcal{J}_2 (for d \equiv 5 \pmod{6}) is used.

For example, the shortcut function associated with the 3n + 1 system is:

To demonstrate that this function is indeed a shortcut function, let us consider 17 as an example.

First, we convert 17 to its index: \dfrac{17-2}{3} = 5 (We subtract 2 when using \mathcal{J}_1 and 1 when using \mathcal{J}_2)

The trajectory of 5 under \mathcal{J}_{1} is:

5 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 6 \rightarrow 1 \rightarrow 2 \rightarrow 0

Multiply each value in the trajectory by 3 and add 2.

17 \rightarrow 26 \rightarrow 20 \rightarrow 5 \rightarrow 8 \rightarrow 2

Now the trajectory of 17 under Terras map defined as

is:

\mathbf{17} \rightarrow \mathbf{26} \rightarrow 13 \rightarrow \mathbf{20} \rightarrow 10 \rightarrow \mathbf{5} \rightarrow \mathbf{8} \rightarrow 4 \rightarrow \mathbf{2} \rightarrow 1

As we can see, we hit the same values as before.

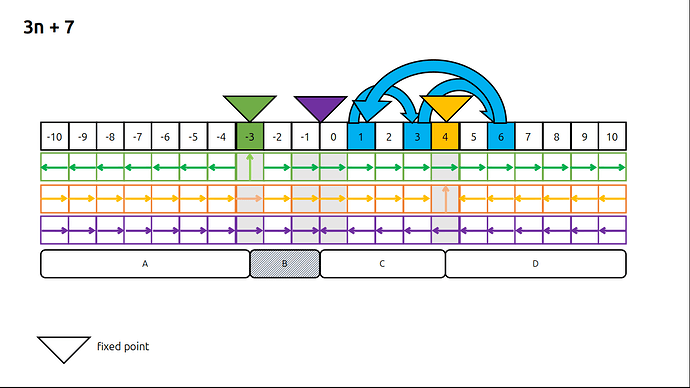

An alternative phrasing of the Collatz conjecture uses the function \mathcal{J}: \mathbb{N} \to \mathbb{N} defined by:

The conjecture then states that for every n \in \mathbb{N}, repeated iteration of \mathcal{J} eventually reaches \mathbf{0}.